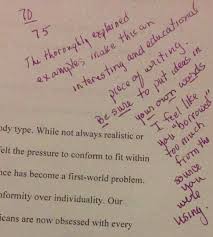

Writing Comments on Students’ Papers starts by addressing a fundamental problem in the teachers’ approach to students’ essays. It points out that teachers must not only be judges of their students’ writing skills, but also coaches that encourage improvement by their learners. The author cites studies showing that students are not comfortable with harsh feedback on their papers. Instead, they prefer comments that focus on the positive elements as well, leaving room for criticism and encouragement. This preference from students can be confirmed by studies on the brain that suggest that learning depends on the emotional state of the learner, and thus encouragement is shown to be crucial. The author recommends that teachers must remember their purpose when commenting on their students’ essays: their function is not merely to point out mistakes but enhancing their students’ chances of improving.

The text suggests that the point of revisions is not merely to edit a text multiple times, its purpose is to rethink the text. Through the hard work of seeing the same text multiple times, experienced writers are able to compose their texts. While allowing many revisions, teachers must be sure that the composition process will stimulate their learners. The text claims that a good strategy is commenting on late-stage drafts, since the students would have experienced the benefits of peer review. Another strategy discussed is allowing rewrites even after the “finished” paper has been submitted. By allowing rewrites, teachers can be more rigorous in their grading, since students will have the opportunity of improving their papers. This strategy can reshape teachers’ orientation, as the drafts become elements to discuss instead of just correct.

While the teacher responds to the student’s drafts, she or he must address only a limited amount of questions. The teacher can begin by encouraging improvement on higher-order issues, such as the overall clarity of the text, only focusing on lower-order issues, such as spelling, when the student successfully handles the structural ones. The text, therefore, argues that the teacher must tell the student that he or she is on the wrong track if their draft does not follow the assignment, which is a higher-order issue. Rather than grading this draft, the teacher could just recommend that the student reread the assignment instructions carefully. Another higher-order issue is the thesis of the paper. Some papers hide their thesis until their end, leaving the reader unable to tell what are the writer’s main points, which suggests that the writer followed his or her way of discussing their ideas without much consideration to the reader. Instead, a reader-based approach will introduce the problems to be discussed, clearly stating the thesis, briefly presenting the whole argument of the essay.

Once the thesis and arguments are adequately exposed, the paper must be discussed when it comes to the supporting ideas and evidence that its author employs. Attention to the complexity of the ideas presented is also important, as well as finding whether the writer left room for opposing views. When the essay finally presents complexity in its ideas, showing a dialogue between evidence and arguments, it also needs to be well organized. This means thinking about main elements of the text, such as the title and paragraphs. The text presents some questions to be asked: is it easy to point the purpose of each paragraph and whether they are coherent? The key point is that each section of the paper has a important function: even a good title can facilitate comprehension, as it can show the reader the writer’s purpose. The same applies to a good introduction. The paper must orient the reader. Therefore, teachers must comment on titles and introductions, as this strategy can show them the importance of these sections to the overall clarification of the essay.

Topic sentences are also important tools to orient the reader. The sentence that starts a new paragraph must expose the writer’s specific view. They are crucial elements, which often makes necessary to change a whole paragraph once they are modified. Paragraphs also need to employ transition words, such as “therefore” and “on the other hand,” in order to connect or contrast different points. Information, another higher-order issue, must be presented carefully. Old information must be addressed in the beginning of the sentence, whereas new information is presented later. This mechanism also orients the reader, since it connects new ideas to the ones already read in the same text. The author calls this method the old/new contract, a strategy that helps the reader to make sense of new information by relating it to what they already know. Therefore, the thesis usually comes at the end of the introduction, because the thesis presents new information, whereas the rest of the introduction focuses on old information.

Once those higher-order issues are adequately addressed, the lower-order issues must be verified. Calling them lower-order concerns does not mean that they are not relevant to the reader. Errors concerning grammar and spelling can be difficult to revise, and the author claims that it is a good strategy to instruct students to be responsible for correcting those types of errors, which saves the teacher from becoming a proofreader. Finally, the text points to the necessity of end comments to encourage revision instead of justifying a grade. In the author’s own words, the mission is to move the draft toward excellence.